Introduction

Audits ensure the integrity and trustworthiness of the global financial system.

Without audits, specifically independent external audits, any company could report whatever figures it wished, with no basis in reality.

No one would invest, no one would lend, no one would employ – the entire system of commerce would grind to a halt. This shows how vitally important audits are.

It’s against this backdrop that we present the Ultimate Guide to Audit: everything you need to know about audits, from beginning to end.

We’ve also made sure to include the latest developments in the audit world, including artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), automation and more.

We’ll start off by revisiting the fundamentals of audits.

Understanding Audit Fundamentals

Objectives of an Audit

The objective of an audit is to provide assurance to users of financial statements that the financial statements are fairly presented in accordance with the applicable financial reporting framework such as generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Auditors seek to determine that financial statements are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error.

Differentiating between Internal and External Audits

Internal audits are conducted by employees of the organization being audited. External audits are conducted by independent auditors who are independent of – i.e. not affiliated with – the organization being audited.

Internal audits are typically focused on providing assurance to management and the board of directors about the effectiveness of the organization’s internal controls. External audits are typically focused on providing assurance to investors and other users of financial statements about the fairness of the organization’s financial statements.

Types of Audits

While most references to “audits” refer to external audits, there are several types of audits that are possible. These include:

- Financial audits are conducted to assess the fairness of an organization’s financial statements. They are typically conducted by external auditors, and are required by law for public companies.

- Operational audits are conducted to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of an organization’s operations. They can be conducted by internal or external auditors, and are often used to identify areas where improvements can be made.

- Compliance audits are conducted to assess whether an organization is complying with laws, regulations, and other contractual obligations. They can be conducted by internal or external auditors, and are often required by regulators.

- Forensic audits are conducted to investigate allegations of fraud or other criminal activity. They are typically conducted by external auditors, and may be used to collect evidence for legal proceedings.

Audit standards and regulations

International Auditing Standards

The International Standards on Auditing (ISA), issued by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB), serve as the global benchmark for audit professionals. ISA ensures consistency and quality in audit engagements on a worldwide scale. Auditors must follow ISA guidelines to maintain the integrity and reliability of financial statements. These standards provide a framework that covers everything from audit planning and risk assessment to audit evidence and reporting.

ISA comprises a set of principles and procedures that address various aspects of an audit, ensuring that auditors systematically evaluate the financial information presented by an entity. It emphasizes the need for independence, professional skepticism, and an in-depth understanding of the audited entity’s business environment. Additionally, it incorporates the concept of materiality, where auditors focus on detecting significant misstatements in financial statements that could impact stakeholders’ decisions.

National Auditing Standards (GAAS)

While international standards set a broad framework, individual countries often have their own sets of Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS). For example, in the United States, the Generally Accepted Auditing Standards are established by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). These national standards complement the international ones and provide more specific guidance tailored to the regulatory environment and business practices of a particular country.

Then there is the PCAOB (Public Company Accounting Oversight Board), a regulatory body established in the U.S. to oversee audits of public companies and broker-dealers, setting standards and conducting inspections of audit firms

The Importance of Compliance with Audit Regulations

Compliance with audit regulations is not a mere formality; it is the bedrock upon which the credibility of financial reporting rests. Auditors must adhere to these regulations rigorously to instill trust in financial statements. Failure to do so can result in legal consequences, reputational damage, and erosion of investor confidence.

One key reason for the importance of compliance is the assurance it provides to stakeholders. Auditors serve as independent third-party watchdogs, verifying that financial statements accurately represent an entity’s financial position, performance, and cash flows. By following audit regulations, auditors help mitigate the risk of financial misstatements and fraud, which are detrimental to the company itself, investors, creditors, and the financial system as a whole.

Compliance with audit regulations also enhances the comparability of financial statements. When audits adhere to established standards, users of financial statements can more easily compare the financial performance and position of different entities, even across borders. This comparability is essential for making informed investment decisions.

External Audit Process

External audits are a systematic and structured examination of an entity’s financial statements and internal controls by an independent auditor. This section provides an in-depth walkthrough of the external audit process, encompassing planning, execution, and reporting.

Audit Planning

Step 1: Preliminary Engagement Activities

- The auditor initiates the engagement by understanding the client’s business, industry, and regulatory environment.

- Establish a clear understanding of the scope, objectives, and terms of the audit engagement.

- Assess any potential conflicts of interest and confirm the auditor’s independence.

Step 2: Risk Assessment

- Identify and evaluate the risk factors that could impact the financial statements, including fraud risks.

- Develop a risk assessment matrix to prioritize areas of audit focus.

- Plan procedures to address identified risks, including substantive tests and tests of controls.

Step 3: Audit Strategy and Plan

- Develop an audit strategy outlining the overall approach for the engagement.

- Create a detailed audit plan that includes audit procedures, timelines, and allocation of resources.

- Consider materiality thresholds and sampling methodologies.

Audit Execution

Step 4: Internal Controls Testing

- Assess and document the effectiveness of the entity’s internal controls over financial reporting (ICFR).

- Test controls relevant to financial statement assertions, ensuring they are designed and operating effectively.

- Identify any control deficiencies and assess their impact on the audit.

Step 5: Substantive Testing

- Conduct substantive tests of transactions, balances, and disclosures to detect material misstatements.

- Use various audit techniques, such as analytical procedures, inquiry, observation, and reperformance.

- Document the audit evidence obtained, including sample sizes and results.

Step 6: Audit Sampling

- Apply statistical or non-statistical sampling methods as appropriate.

- Ensure that the sample is representative and sufficiently sized to draw meaningful conclusions.

- Evaluate the results of the sample and extrapolate to the entire population, assessing the risk of sampling error.

Step 7: Audit Documentation

- Maintain detailed audit documentation, including work papers, to support findings and conclusions.

- Include a clear link between the audit plan, procedures performed, evidence obtained, and conclusions reached.

- Comply with professional standards for audit documentation.

Reporting

Step 8: Evaluation and Conclusion

- Assess the results of the audit procedures and determine whether the financial statements are materially misstated.

- Consider any identified deficiencies in internal controls and their implications on financial reporting.

- Formulate an overall audit opinion based on the evidence gathered.

Step 9: Audit Report

- Prepare the audit report in accordance with relevant audit standards and regulations.

- Clearly state the auditor’s opinion on the fairness of the financial statements.

- Include any explanatory paragraphs or emphasis-of-matter paragraphs, if necessary.

Step 10: Post-Reporting Activities

- Communicate with the client’s management and board of directors regarding audit findings and recommendations.

- Address any unresolved issues or disagreements with the client.

- Retain the audit documentation in accordance with professional standards.

Best Practices

While the audit process is relatively standardized, there are areas of best practice that leading auditors incorporate into their audit process:

- Maintain open and effective communication with the client throughout the audit process.

- Continuously update the audit plan as new information emerges or circumstances change.

- Seek input and insights from audit team members, particularly regarding areas of expertise.

- Stay current with changes in auditing standards and regulations.

- Utilize modern AI-powered automated accounting and auditing software to minimize risk and maximize compliance.

Audit Evidence and Documentation

Audit Evidence and Its Significance

Audit evidence refers to the information and documentation obtained by auditors during the audit process. This evidence is essential for auditors to form conclusions and opinions on the financial statements’ accuracy, completeness, and compliance with accounting standards and regulations. Audit evidence is critical because it substantiates the auditor’s findings and supports the ultimate audit opinion.

Types of Audit Evidence:

- Documentary Evidence: This includes financial statements, invoices, contracts, and other written records.

- Physical Evidence: Tangible assets, such as inventory or equipment, can be physically inspected.

- Oral Evidence: Information obtained through inquiries and discussions with management and staff.

- Analytical Evidence: This involves using analytical procedures to assess the reasonableness of financial statement figures.

- Third-party Evidence: Confirmations from external parties, like banks and suppliers, provide independent verification.

Proper Documentation and Record-Keeping

Accurate and organized documentation is crucial for a successful audit. Here are some guidelines for proper audit documentation and record-keeping:

- Clear and Comprehensive: Documentation should be clear, complete, and well-organized. It should enable someone else to understand the audit work performed.

- Timely Recording: Document audit procedures, findings, and conclusions as they occur during the audit, ensuring timely recording of evidence.

- Cross-Referencing: Establish clear links between audit objectives, procedures performed, and the evidence obtained. This cross-referencing aids in understanding the audit trail.

- Professional Judgment: Document the auditor’s professional judgment, including the basis for significant estimates and assumptions.

- Workpapers: Maintain detailed workpapers, including checklists, schedules, and analytical procedures. These should be preserved for a specified period per professional standards.

- Retention and Security: Safeguard audit documentation to protect it from loss, damage, or unauthorized access.

- Electronic Documentation: When using electronic tools for documentation, follow data security and retention policies.

Risk Assessment and Materiality

Audit Risk

Audit risk is the risk that an auditor may issue an incorrect opinion on an entity’s financial statements, either by failing to detect material misstatements or by incorrectly concluding that they exist when they do not. It comprises three components: inherent risk, control risk, and detection risk.

- Inherent Risk: This is the susceptibility of financial statements to material misstatement without considering the effectiveness of internal controls. Factors that contribute to inherent risk include the complexity of transactions, industry-specific risks, and the entity’s financial stability.

- Control Risk: Control risk is the risk that internal controls will not prevent or detect material misstatements. Auditors assess the design and effectiveness of internal controls to determine control risk. Weak or inadequate controls increase the likelihood of material misstatements.

- Detection Risk: Detection risk is the risk that auditors’ procedures will not detect a material misstatement that exists. It is the only risk component that auditors have direct control over. Auditors can adjust the nature, timing, and extent of their procedures to manage detection risk.

Materiality and Its Impact

Materiality is a crucial concept in auditing. It refers to the threshold beyond which a misstatement in the financial statements could influence the economic decisions of users. Materiality is both quantitative and qualitative, taking into account the dollar amount, nature, and context of misstatements.

Materiality plays a significant role in audit decisions:

- Audit Planning: Auditors set materiality levels to determine the scope of their audit procedures. Lower materiality thresholds require more extensive testing.

- Risk Assessment: Materiality is considered when assessing inherent risk and control risk. More significant materiality levels may lead to higher assessed risks.

- Sampling: Auditors use materiality to determine sample sizes for substantive testing. Smaller materiality levels necessitate larger samples.

- Audit Opinion: If auditors identify material misstatements, they may issue a qualified or adverse opinion, highlighting the misstatements’ significance.

Sampling in Auditing

Sampling techniques are essential tools in the auditor’s toolkit, allowing auditors to draw conclusions about an entire population of transactions or items by examining a representative subset. Sampling serves to make audits more efficient and cost-effective while maintaining a high level of assurance. Here, we explore the use of sampling techniques in auditing and methods for selecting samples and ensuring their representativeness.

Use of Sampling Techniques

In auditing, it is often impractical or too costly to examine every transaction or item within a population. Instead, auditors employ sampling to select a subset of items for examination. The key purpose is to obtain sufficient, appropriate audit evidence to support conclusions about the entire population. Sampling is employed in both tests of controls and substantive testing.

Methods for Selecting Samples

- Random Sampling: This method involves selecting items from the population entirely at random. Random sampling ensures that every item in the population has an equal chance of being selected. It is a statistically sound method that helps minimize bias.

- Systematic Sampling: In systematic sampling, auditors select items at regular intervals from the population. For example, if auditing a list of invoices, every 10th invoice might be selected. This method is easy to implement and ensures that the sample is spread evenly throughout the population.

- Stratified Sampling: Stratified sampling involves dividing the population into subgroups or strata based on certain characteristics (e.g., value or location). Auditors then select samples from each stratum in proportion to its size or significance. This method is useful when certain subgroups may carry a higher risk of misstatement.

- Judgmental Sampling: In some cases, auditors may use their judgment to select samples based on their knowledge of the client’s business, industry, or specific risks. While this method lacks the statistical rigor of random or systematic sampling, it can be effective in targeting areas of concern.

Ensuring Representativeness

Representativeness is critical in sampling to ensure that the selected sample accurately reflects the characteristics of the entire population. To achieve this, auditors should ensure that the following elements are present:

- Randomness: Use random or systematic sampling methods to reduce bias and ensure that every item has an equal chance of being selected.

- Adequate Sample Size: Ensure that the sample size is sufficient to draw meaningful conclusions, considering factors like materiality, risk, and expected error rates.

- Documentation: Thoroughly document the sampling methodology, including the rationale for the chosen method and the sample size determination.

- Consistency: Apply the chosen sampling method consistently throughout the audit process to maintain reliability.

Internal Controls and Audit Testing

Role of Internal Controls in Audits

Internal controls are the policies, procedures, and mechanisms put in place by an organization to safeguard its assets, ensure the accuracy of financial reporting, and achieve compliance with laws and regulations. In the context of audits, internal controls play a crucial role in providing the framework within which auditors assess the reliability of financial statements. Effective internal controls reduce the risk of material misstatements and fraud in financial statements.

Auditors evaluate internal controls to determine their design and effectiveness. This assessment serves two main purposes:

- Risk Assessment: Auditors use their understanding of internal controls to assess control risk, which is the risk that internal controls will not prevent or detect material misstatements. If controls are strong and effective, auditors may rely on them and adjust their audit procedures accordingly.

- Substantive Testing: Even when relying on internal controls, auditors perform substantive testing to obtain direct audit evidence about the accuracy and completeness of transactions and account balances.

Audit Testing Procedures and Their Significance

Audit testing procedures are the specific steps auditors undertake to gather evidence about the financial statements and internal controls. These procedures fall into two main categories: tests of controls and substantive tests.

- Tests of Controls: These procedures assess the design and operating effectiveness of internal controls. Auditors use tests of controls to determine if controls are designed appropriately and whether they are functioning as intended. A positive outcome in tests of controls may lead to a reduced need for substantive testing.

- Substantive Tests: Substantive testing aims to detect material misstatements in financial statements. Auditors perform substantive tests on transactions, account balances, and disclosures. They include procedures such as analytical review, detailed testing, and sampling to obtain sufficient and appropriate evidence.

Audit testing is significant because it allows auditors to provide an independent assessment of the accuracy and reliability of financial statements. It helps auditors form conclusions about whether the financial statements are free from material misstatements and whether internal controls are effective in mitigating risks. Ultimately, audit testing is the means by which auditors fulfill their responsibility to provide assurance to stakeholders and maintain the credibility of financial reporting.

Fraud Detection and Prevention in Audits

Detecting and preventing fraud is a critical aspect of the audit process, as financial fraud can have severe consequences for an organization and its stakeholders. Auditors play a crucial role in identifying fraud risks and implementing procedures to uncover fraudulent activities.

Prevention is equally essential, as proactive measures can deter fraud from occurring in the first place.

One effective strategy for detecting fraud during audits is to exercise professional skepticism. Auditors should approach the audit with a questioning mindset, considering the possibility of fraud in all areas.

Real-world examples

Real-world examples of red flags include unexplained discrepancies, unusually high or low financial performance, inconsistent documentation, and a lack of supporting evidence for transactions. Auditors should also look for signs of management override of controls, such as journal entries made to manipulate financial statements.

Prevention of fraud involves strengthening internal controls and fostering a culture of ethics and integrity within the organization. This can include implementing segregation of duties to prevent one individual from having too much control over financial processes, conducting regular fraud risk assessments, and establishing a robust whistleblower program.

Audits can also serve as a deterrent by making employees aware of the possibility of detection. Ultimately, a combination of vigilant auditors, effective internal controls, and a commitment to ethical behavior can help organizations detect and prevent fraud.

Reporting and Communication in Auditing

Components of an Audit Report

An audit report is the primary means through which auditors communicate their findings and conclusions to stakeholders. It typically comprises several key components:

- Title: The report begins with a title, which usually includes the word “Independent” to emphasize the auditor’s impartiality.

- Addressee: The report specifies the party to whom it is addressed, typically the entity’s shareholders, board of directors, or regulatory authorities.

- Introductory Paragraph: This section outlines the responsibilities of the auditor and management. It also mentions the financial statements audited and the period covered.

- Scope Paragraph: The scope paragraph explains the extent of the audit work performed. It highlights the audit standards followed, the procedures conducted, and any limitations or restrictions encountered.

- Opinion Paragraph: The most critical part of the audit report, the opinion paragraph, states the auditor’s conclusion regarding the fairness of the financial statements. It can be unqualified (clean opinion), qualified (with exceptions), adverse (material misstatements), or a disclaimer (lack of sufficient evidence).

- Basis for Opinion: In this section, auditors provide details about the audit procedures performed and the evidence obtained to support their opinion. This enhances transparency and helps stakeholders understand the audit process.

- Other Reporting Responsibilities: If applicable, the report may include information about other matters required by auditing standards or regulations, such as reporting on internal controls.

- Auditor’s Signature and Address: The auditor signs the report, indicating their responsibility for the audit, and includes their firm’s address.

- Date of the Report: The report is dated to indicate when it was issued.

Communication of Audit Findings

Effective communication of audit findings is a crucial part of the audit process. Once the audit is complete, auditors communicate their findings and opinions to relevant stakeholders:

- Client Management: Auditors meet with client management to discuss their findings, any identified weaknesses in internal controls, and any recommendations for improvement. This communication can help management address issues promptly.

- Audit Committee: The audit committee of the entity’s board of directors plays a critical role in overseeing the audit process. Auditors typically present their findings and opinions to the audit committee, ensuring independent oversight.

- Shareholders and Investors: The audit report is made available to shareholders and investors as part of the financial statements. It provides them with an independent assessment of the reliability and accuracy of the financial statements.

- Regulators and Authorities: In regulated industries, auditors may be required to communicate their findings and opinions to relevant regulatory authorities. This helps ensure compliance with legal and regulatory requirements.

- Public Disclosure: In many cases, the audit report is publicly disclosed, making it accessible to a wider audience, including potential investors and creditors.

Professional Ethics in Auditing

Professional ethics are the cornerstone of the auditing profession, and they play a fundamental role in maintaining the integrity and credibility of financial reporting. Ethical behavior is not merely a legal requirement but a moral obligation for auditors. The importance of ethics in auditing cannot be overstated, as auditors are entrusted with the responsibility of providing independent and unbiased assurance to stakeholders.

Key ethical principles and challenges

Key ethical principles that guide auditors include integrity, objectivity, professional competence, and due care, confidentiality, and professional behavior.

Integrity demands honesty and truthfulness in all professional matters. Objectivity requires auditors to approach their work without bias, conflicts of interest, or undue influence from others. Professional competence and due care mandate continuous learning and the application of professional knowledge and skill. Confidentiality obligates auditors to protect sensitive client information, and professional behavior requires auditors to act in a manner that upholds the reputation of the profession.

Ethical challenges in auditing may arise when auditors face pressure to compromise their independence, when dealing with management’s expectations, or when encountering financial incentives to overlook irregularities. Such challenges require auditors to make difficult choices and adhere to their ethical principles. The consequences of ethical lapses can be severe, eroding trust in the audit profession and damaging the reputation of auditors and the organizations they serve. Therefore, unwavering commitment to professional ethics is not only essential for auditors but also for the sustainability and credibility of the audit profession as a whole.

Emerging Trends in Auditing

Auditing, like many other fields, is experiencing significant transformation due to advances in technology, data analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI). These emerging trends are reshaping audit methodologies and tools, ultimately enhancing the efficiency, accuracy, and effectiveness of audits.

1. Technology-Driven Audit Processes

Technology has revolutionized the way audits are conducted. Auditors are increasingly utilizing specialized audit software and tools that allow for real-time data access and analysis. Cloud-based audit platforms enable remote auditing, enhancing flexibility and collaboration among audit teams, especially in a post-pandemic world.

2. Data Analytics and AI

Data analytics and AI are at the forefront of auditing’s evolution. Auditors are leveraging advanced data analytics techniques to identify patterns, anomalies, and trends within financial data. AI-powered algorithms can process vast datasets quickly, increasing the scope of audit procedures and the detection of irregularities. Predictive analytics are being used to assess the likelihood of fraud or financial misstatements.

3. Blockchain Auditing

As blockchain technology gains prominence in various industries, auditing of blockchain-based transactions and smart contracts is becoming more relevant. Auditors need to adapt to this new technology and develop methodologies for auditing blockchain systems effectively.

4. Robotic Process Automation (RPA)

RPA is being used to automate repetitive audit tasks, such as data extraction and reconciliation. This not only reduces the risk of errors but also allows auditors to focus on higher-value tasks like data analysis and interpretation.

5. Cybersecurity Audits

With the increasing frequency and sophistication of cyberattacks, auditors are paying more attention to cybersecurity audits. This involves evaluating an organization’s information security controls to ensure the protection of sensitive data.

6. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Audits

As sustainability and ESG considerations become more important for investors and stakeholders, auditors are exploring ways to incorporate ESG auditing into their practices. This includes assessing an organization’s environmental impact, social responsibility, and corporate governance practices.

7. Regulatory Compliance and Reporting

Audit methodologies are evolving to keep pace with changing regulatory requirements. Auditors are adapting to new standards, such as updated lease accounting and revenue recognition standards.

Continuing Education and Career Development

Continuing education and career development are paramount for accounting professionals, especially those looking to advance their auditing skills. Staying up-to-date with the latest developments in audit methodologies, standards, and technology is essential.

To further develop their careers, professionals can consider enrolling in specialized auditing courses, pursuing advanced certifications such as the Certified Internal Auditor (CIA) or Certified Information Systems Auditor (CISA), and attending industry conferences and seminars to network and learn from experts.

AI advancements offer a valuable opportunity for career development in auditing. Accounting professionals can leverage AI tools and platforms to enhance their analytical capabilities, automate routine audit tasks, and extract valuable insights from vast datasets. By mastering AI-driven data analytics and machine learning, auditors can not only increase their efficiency but also offer more advanced and sophisticated audit services. Embracing AI as a tool for audit analytics can position professionals at the forefront of the evolving audit landscape, making them more competitive and valuable in the industry.

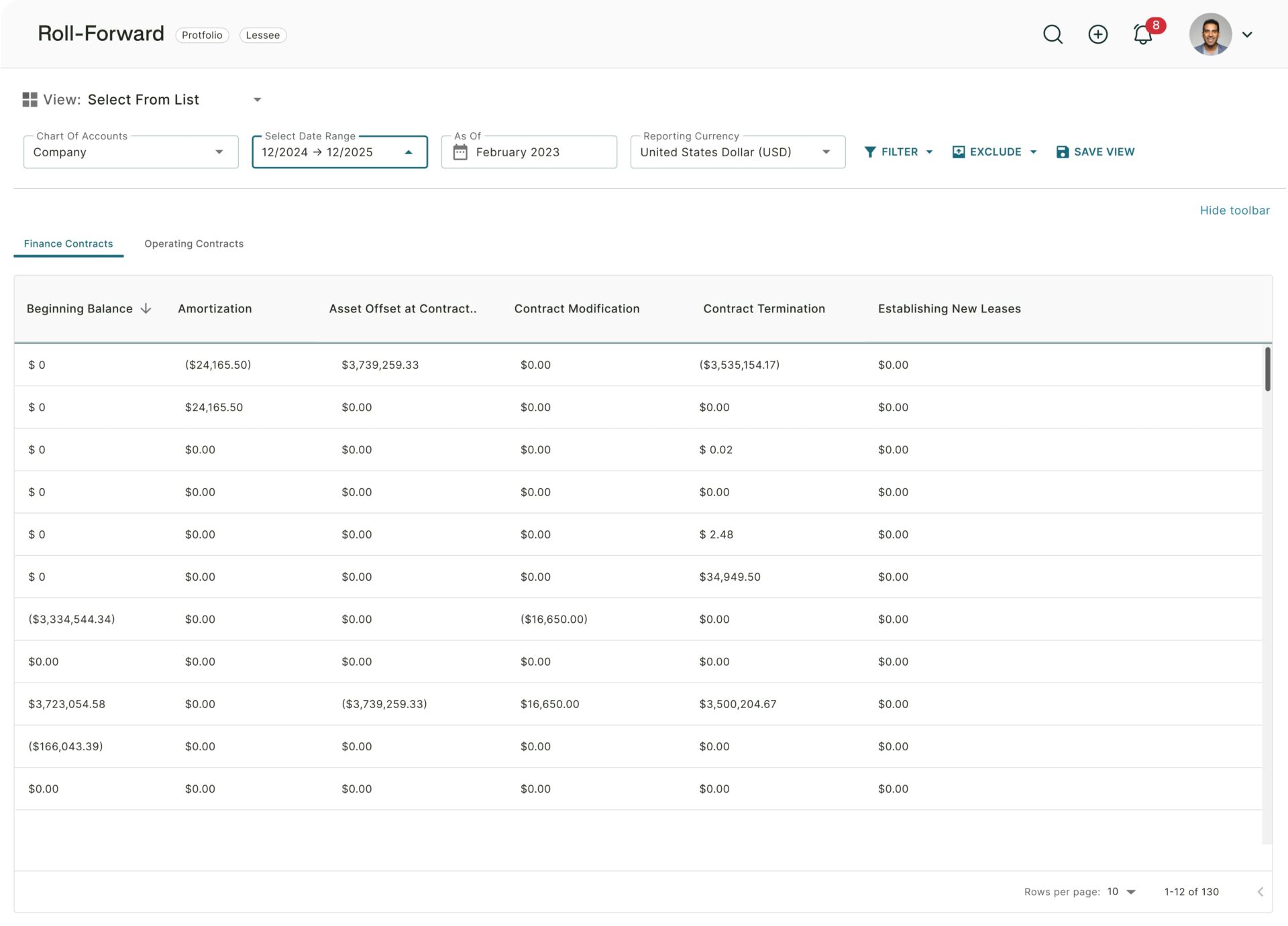

External Audit Software & Automation

Trullion enables audit teams to unlock their full audit potential. Trullion not only helps audit firms save time and money – it empowers audit teams to enhance clients’ audits, provide an elevated experience, and increase trust, adding value throughout the process.

With Trullion, auditors can expect:

A smoother, seamless audit experience: Perform audits in less time, while increasing the quality and accuracy of your reviews and substantive testing with AI-powered automation. A SaaS solution and continuous compliance means you’re always up to date with evolving standards.

To make a strategic impact: Reduce busywork and empower your employees to focus on more high-impact work. This will also result in more employee satisfaction and higher retention.

Increased visibility: From the big picture to the granular details, easily upgrade from endless communication threads and access data at its source, in real-time.

Audit Case Studies

While most audits are relatively straightforward, some offer fascinating instances of complexity that need to be overcome.

Take for example Eisai, Inc., the U.S. subsidiary of Eisai Co., Ltd, a Japanese pharmaceutical company based in Tokyo. While Eisai is a publicly-traded company on the Tokyo stock exchange, the U.S. arm is a private entity comprising approximately 3,000 employees with business operations across the world.

This introduced a tremendous amount of complexity for the accounting teams of the company. Just accounting correctly for leases, which had to comply with the latest lease accounting standards in both GAAP and IFRS, meant hundreds of worksheets and a huge amount of resources required.

The company decided that to remain compliant and audit-ready, a tech-forward solution was required. The company engaged Trullion and hasn’t looked back.

Eisai is now using Trullion on a monthly basis to book the accounting entries, report on leases, reconcile the date of the general ledger, and report IFRS numbers to their corporate parent. On an annual basis, the client utilizes the disclosure features to compile the data needed for annual GAAP financial statements.

Eisai went on to make strategic changes in the way they accounted for leases according to Trullion’s calculations, valuing the audit trail provided by the solution.

Vincent Shurr, Global Director of Corporate Accounting and Consolidations at Eisai, explains that the system “handled leasehold improvements a little differently than our Excel models and we ultimately proved to ourselves and Deloitte that Trullion is performing an accurate ASC 842 and converted.”

Conclusion: Audit Is More Critical Than Ever in Maintaining Financial Stability

As we’ve seen, audits are rigorous processes that aim to establish that a company’s financial results accurately represent its financial position, performance, and cash flows, by complying with the relevant financial reporting standards.

Delving deeper, we looked at:

- Understanding audit fundamentals

- Types of audits

- Audit Standards and Regulations

- External audit processes

- Audit evidence

- Materiality and its central importance

- Plus case studies, ethics, and more

Perhaps most excitingly, we looked at the future of audit, as it harnesses technology to add more value to audit teams and their clients.

To learn more about incorporating Trullion’s advanced technology into your accounting and auditing processes, connect with Trullion today.